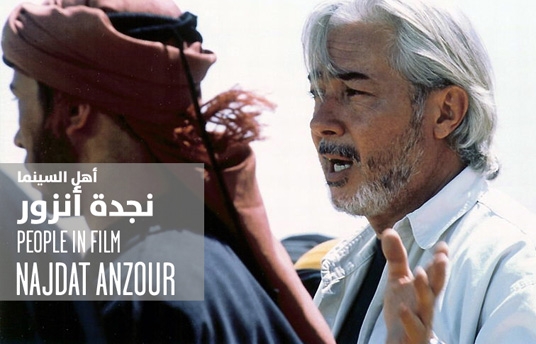

أهل السينما:نجدة أنزور

23 أغسطس 2011

ولد نجدة أنزور في مدينة حلب عام 1954، وتخرج من جامعتها بعد أن تخصص في الهندسة الميكانيكية. إنه ابن المخرج اسماعيل أنزور الذي أخرج أول فيلم سوري وكان له الأثر الأكبر في توجهه الفني، وقاد خطاه في السينما والفن.

أخرج أول إعلان تلفزيوني له حين كان في الثامنة عشر من عمره، وعمل في الأردن لأكثر من 15 عاماً، حيث أخرج عدداً من المشاريع التي لاقت نجاحاً باهراً. فاز فيلمه الطويل الأول ‘نزهة على الرمال’ بالجائزة البرونزية في مهرجان بغداد العالمي الأول للتلفزيون عام 1987.

شارك أول فيلم سينمائي أردني أخرجه ‘حكاية شرقية’ 23 مهرجاناً عالمياً وحصل على العديد من الجوائز.

عاد إلى سورية عام 1994 وعمل في بداية عصر نهضة الدراما السورية وكان مؤسساً للمدرسة البصرية في الفن التلفزيوني. أخرج عام 1994 مسلسله الشهير ‘نهاية رجل شجاع’ الذي يعتبر نقلة نوعية في تاريخ الدراما العربية.

فاز فيلمه الوثائقي ‘البحث عن …’ بالجائزة الفضية في مهرجان الجزيرة الأول للأفلام الوثائقية التسجيلية.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: كونك ابن اسماعيل أنزور، مخرج الفيلم السوري الصامت الأول عام 1932 ‘تحت سماء دمشق’. ما الذي ورثته عن والدك كمخرج سينمائي؟

نجدة: أعتقد أن والدي استطاع أن يلفت الانتباه في زمن صعب هو بدايات القرن إلى أهمية السينما في حضارة الشعوب. تصوري شاباً يدرس السينما عام 1922 أكيد هو مختلف عن جيله. لذا أحاول أن أكون مختلفاً عن جيلي وأحمل همومه إلى العالمية.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: بما أننا في شهر رمضان، أخبرنا عن أعمالك الرمضانية هذا الموسم.

نجدة: في هذا الموسم قدمت عمليْن مختلفيْن. الأول ‘في حضرة الغياب’ عن سيرة الشاعر الفلسطيني الكبير محمود درويش وهو يُعرض على قنوات عربية ومصرية عدة.

أما العمل الآخر ‘شيفون’ من تأليف وسيناريو وحوار د. هالة دياب وبطولة نخبة من الوجوه الشابة والذين يظهرون على الشاشة للمرة الأولى وهي تجربة جديدة في الدراما شكلاً ومضموناً، وسيعرض هذا العمل بعد شهر رمضان مباشرة.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: لسوء الحظ، نحن لا نشهد هذا الكم الكبير من المسلسلات التلفزيونية إلا في شهر رمضان. ما هو رأيك بهذه الظاهرة؟ وما سببها؟

نجدة: إن السياسة البرامجية الخاطئة في محطات التلفزيون العربية هي السبب المباشر في تكثيف عرض المسلسلات العربية على الشاشة من باب المنافسة، كما يدعون. وهذا ما حوّل المخرج والمنتج إلى “مخرجي ومنتجي رمضان” وباقي السنة هي أعمال معادة ومكرّرة بالإضافة إلى المسلسلات المدبلجة التركية وغيرها.

أنا أرى أنه يجب أن يكون هناك موسم مواز لرمضان تعرض فيه الأعمال الهامة وتقدم لها الدعاية والرعاية اللازمة لكي نستطيع أن نتحرر من فكرة العرض الرمضاني. في النهاية هي مسؤولية العرض وليس الإنتاج.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: أين تجد نفسك أكثر؟ المسلسلات أم السينما؟ نجدة: كل ما قدمت في التلفزيون هو تمهيد إلى سينما متطورة قادمة. والمحاولة الكبيرة كانت الفيلم العالمي ‘سنوات العذاب’ الذي يقدم جانباً مدهشاً من الظروف التي عاش فيها الشعب الليبي خلال فترة الاحتلال الإيطالي. وقد عملت على هذا المشروع لأكثر من سنتين وبدأنا بتصويره في إحدى الجزر الإيطالية بمشاركة نخبة من الفنيين العالميين وفجأة توقف المشروع لأسباب غير معلنة وأعتقد بأنها سياسية ترافقت مع التقارب الليبي الايطالي.مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: فاجأت الجماهير العربية بالتطرّق إلى موضوعات جريئة من انتقاد للتطرف بكل أشكاله كما في المسلسلات ‘حور العين’ و‘المارقون’. ما الذي تحاول قوله؟

نجدة: في أعمالي الأخيرة من ‘الحور العين’ و ‘المارقون’ و‘سقف العالم’ و‘ما ملكت ايمانكم’ نحاول تقديم الإسلام المعتدل الذي ينبذ العنف ويدعو للتعايش والحوار البناء. نحاول تلمس الطريق أمام هذا الجيل الذي يتسرب من أصابعنا كحبات الرمل. أعتقد بأننا نجحنا في ذلك وكان تأثير هذه الأعمال كبيراً على شريحة واسعة من الجمهور العربي. هذا ما دفعنا هذا العام لتقديم مسلسل ‘شيفون’ الجريء والمختلف، رغم وجود بعض العقبات الرقابية على مستوى المحطات العربية.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: لديك ميل نحو الدراما التاريخية، كيف تقيّم شعبية هذا النوع في هذه الأيام؟

نجدة: قدمت الكثير من الأعمال التاريخية الناجحة مثل ‘الجوارح‘و ‘الكواسر’ و‘الموت القادم من الشرق’ و‘فارس بني مروان‘، و‘سقف العالم’ و‘تل الرماد‘، و‘إخوة التراب‘، و‘نهاية رجل شجاع’ وغيرها من الأعمال التي تركت بصمة فنية مدهشة وفتحت الطريق أمام الدراما السورية للانتشار والنجاح. أعتقد أن العمل سواءً كان تاريخياً أو معاصراً، عندما يقدم موضوعاً مختلفاً وجريئاً ومفيداً هو الهدف الذي أسعى إليه. ما ساهم في نجاح الدراما السورية هي والوجوه الجديدة والمواقع المميزة والإتقان الإنتاجي والإخلاص وحب المهنة والتآخي بين الفنانين. نخشى اليوم أن نفقد تلك الصفات ونتحول كما يريد البعض إلى منتجين هدفنا الربح وتشويه المجتمع وتحقيق أجندات لا تمت لمجتمعنا بصلة.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: ما هي أبرز المشاكل التي تواجهك كمخرج سوري؟

نجدة: المشاكل الحقيقية هي التسويق والتحكم بالمنتج الفني من قبل جهات ليس لديها الهم الفني.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: هل سنشهد عودتك الى السينما قريباً؟

نجدة: عودتي إلى السينما قريبة في مشروع فيلم سينمائي عالمي أعمل عليه منذ فترة وأتمنى ألا يخضع هذا العمل إلى أمزجة سياسية أو غيرها، فأنا أتوق إلى تقديم فيلم سينمائي عربي يساهم في تقديم مجتمعنا العربي إلى العالمية.

مؤسسة الدوحة للأفلام: ما هي الرسالة التي ترغب بتوجيهها للشباب العربي الذي يرغب بدخول المجال الاعلامي؟

نجدة: تمر سورية والمنطقة عموماً بظروف سياسية معقدة ولا بد أن ينعكس ذلك على الانتاج التلفزيوني الذي يعتمد بالأساس على التسويق إلى المحطات العربية. ولا بد أن يكون هناك تأثيرٌ سياسي في عملية الإختيار وخاصة في المحطات الخليجية، والتي على ما يبدو أن هناك قراراً غير معلن بعدم شراء الأعمال الدرامية السورية، إلا ما أتفق عليه مسبقاً أو كانت مشاركة في إنتاجها. هذاانعكس بشكل سلبي على عملية التسويق وهذا المشهد سيفرز نتائج ربما تكون سلبية على الإنتاج الدرامي السوري عموماً في الموسم القادم، فحصار الدراما السورية ليس بجديد. لكن هذه المرة يبدو أنه سيأخذ أشكالاً عنيفة ومختلفة وربما سيكون لها أثراً على مضمون تلك الأعمال من الناحية الفكرية، فالخيارات أصبحت صعبة وخاصة أمام القطاع الخاص. أنصح شبابنا العربي الذي يدرس الإعلام أن ينطلق من وطنية ويعلنها وأن لا يخشى من تقديم نفسه كعربي إعلامي ومعاصر يحافظ على الثوابت ويبحث عن مستقبل أفضل.