Cinema as discourse in understanding humanity: Qumra Master Lav Diaz

Apr 07, 2025

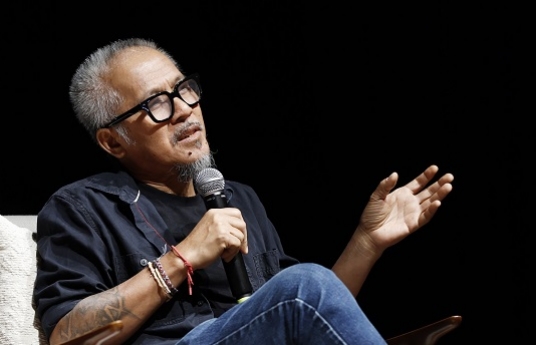

Doha, Qatar; April 7, 2025: Qumra Master Lav Diaz, the acclaimed Filipino filmmaker known for meditative works that explore his nation’s authentic soul and its chequered history discussed cinema as discourse in understanding humanity.

At his Masterclass at Qumra, the annual talent incubator event by Doha Film Institute, Diaz referenced the brutality of dictatorships that crushed his country weighed on his words, drawing parallels in today’s world – lamenting that the “walls of ignorance are getting thicker and higher…”

Adding that “humanity’s struggles are getting darker,” he urged filmmakers to “act fast.” He said cinema is poetry, a reflection of the reality we are harbouring,” and for him, ‘creating art is a spiritual thing; I made films trying to understand and explore the Filipino soul. The Filipino perspective shaped by its history is very problematic and I understand it and don’t understand it at the same time.”

Diaz said he grew up in a family that revered books– in particular, Russian books, which were part of the legacy of his social worker and teacher father. He grew up reading classics by Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy, which are clear influences in his films, including The Woman Who Left (2016), which was inspired by Tolstoy’s short story, ‘God Sees the Truth, But Waits. The film won the Golden Lion at the 73rd Venice International Film Festival.

Diaz grew up watching movies at cinemas on weekends in a nearby town. “I got an overload of those images in my head, and cinema came naturally to me.” The tumultuous events of the late 1960s and the rise to power of Ferdinand Marcos defined the filmmaker in him.

“The place I called paradise had become a nightmare,” recalled Diaz, with the biggest influence in him being acclaimed filmmaker Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975). “I was shocked watching it; it was the first socially conscious Filipino cinema. It changed my concept and outlook about the medium, and how to use cinema to change people.”

While Diaz would go on to work on the pito-pito movies (seven-seven movies: seven days to shoot, seven days for post-production), moving to the US to work as a journalist for the Filipino Daily Express in New Jersey transformed his life as a filmmaker. His a five-hour-long film West Side Avenue (2001) documented the Filipino diaspora in the US, and would define his own philosophy and notions about time and space in cinema.

Diaz said he does not live by the definitions of fiction and documentary, adding that “both tell stories, fiction mirrors reality.”

He said people in the Philippines – and many Southeast Asian nations – have a very different perspective of time and space. “We are a storm-battered country, with nature as a nemesis; space is destroyed by strong typhoons and time is waiting for them to end – just like waiting for the corruption in our country to end.”

In his films like the 11 hour long Evolution of a Filipino Family (2006), which took 10 years to make, his approach is to “enter the universe of cinema so you can see life. Don’t manipulate it. You have to just show and experience life.”

Diaz sees cinema as ‘work in exile – it is a lonely, lonely journey’. “You lose track of reality, do poetry, go back to reality. It is with the cycles of life.”

Commenting on Qumra 2025’s positive impact on the industry, he said: “Doha Film Institute has existed for 15 years and has already done a lot for the region’s cinema. Qumra is very progressive and has made many strides in terms of creating and pushing cinema. The fact that some of the biggest distributors and programmers are present here is something great… especially for young filmmakers.”

His advice on making films is “to just do it. Do it alone. Struggle. Deal with life and poetry, bring them together and continue to make films.”