People in Film: Mohamad Malas

Aug 16, 2011

Mohamad Malas was born in 1945 and studied filmmaking in V.G.I.K. Moscow from 1969 to 1974. Soon after, he directed ‘Al Quneitra 74’ and ‘The Memory and Furat’. From 1984 on, Malas directed many films including ‘The Dreams of the City’ (1984), ‘The Night’ (1992), ‘On the Sands, Under the Sun’ (1998) ’Passion’ (2004) and ‘Al Mahhed’ (2007). ‘The Dreams of the City’ received many awards such as the prestigious Golden Palm at the 1984 Cannes Festival. ‘The Night’ won the first award at several festivals including The Freibourg Festival, Switzerland and The Bruges Festival, Belgium, in 1993.

DFI: Tell us more about yourself. your previous works, awards, etc…

Mohamad: I make films to tell people about myself! And when making a film is not possible in my country, I tell people about myself through writing and literature.

I have been to schools to learn reading and writing, to get to know myself better. Then I studied philosophy in college to be able to better understand life and men. Meanwhile, without being aware, I fell in love with picture. So I studied filmmaking, which has become my way and tool of self-expression.

Ever since I made my first short film at the film institute in Moscow, I realized that I make films to look for what is “missing” in my life. I was never able to abandon my need for what is “missing”. I stopped looking for it because I did not want to betray myself… but I tried to make it happen in films.

The missing elements that I try to find in reality are – times and places in my country that I greatly miss, after all, the life I have lived. That is why I use my own memories and the collective memory of my people, to convey the views I have in mind.

When I wrote my first feature film’s screenplay ‘Ahlam Al Madina’ (dreams of a city) in 1982, I never intended to shed light on the prevalent democratic environment. But when I finished the film, I realized that this was what was ‘missing’, that this was what I was trying to look for.

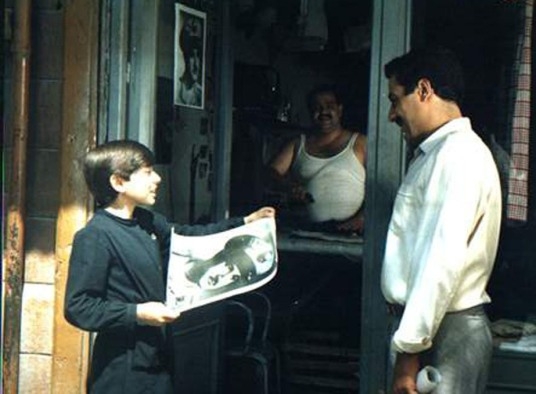

Scene from the movie 'Ahlam Al Madina'.

And at the time I made my feature film ‘The Night’, I was looking for my hometown, but instead I found a village that was shattered by the Israeli bombing of Quneitra city, so I wanted to rebuild it. I could not achieve that except in cinema, where I did build it, and started living in it.

In ‘Passion’, I wanted to look for freedom, through the character of a woman who loves to sing, but was murdered by her parents who had doubts about her reputation.

I wrote my current project ‘Namou Cinema’ before the ongoing demonstrations ever started. I have never expected anything like our young generation revolting for ‘dignity’ against the Syrian regime. But I had written it, while trying to look for what was missing in the Syrian young generation’s world, wondering where are we heading…when this would all be over?

DFI: Congratulations on your DFI grant. Can you tell us more about this new film? And when will we be watching it?

Mohamad: It is a film titled ‘Namou Cinema’, and DFI’s grant was a great help to bring it to the screen. This film is a continuation of my journey. The difference is that I express my views on the young generation in Syria and their potential fates in this situation that offers them nothing.

The current events in Syria have urged me to re-think the project all over again, in order to give it a more realistic dimension that shapes a better the message behind it.

Needless to say that the current situation in Syria has made it real hard for us to shoot the film, but if I can acquire another producer besides DFI, I believe we can expect to watch it in the fall, next year.

DFI: You are one of the pioneers of cinema d’auteur in the region, with international recognition. What is it that highlights the themes of your films?

Mohamad: I am not one of the pioneers. There are great pioneers in the Arab cinema, whom I’ve learnt from… maybe I am one of the pioneers of those who have chosen the cinema d’auteur to portrait the reality of the Syrian society.

I think what has incited this Arab and international interest in my films is the “harmony” that exists between my own memory and the collective memory. What characterizes the subjects of these films is their connectivity and warmth and relevance to people, in addition to the honesty in portraying these subjects.

DFI: Acclaimed critics have labeled your films as a journey of visual poetry. What technique do you apply in your storytelling process?

Mohamad: I know that my films are a journey in my inner world, aiming to find emotions and things that I need in order to live freely and in dignity in this situation we are in. I have rationalized this world very well through experience not through books and tales, because I started my life working as a laborer amongst modest people.

I did not use “techniques” to express this experience, but instead I have used honesty, courage and ambition to tell a story.

DFI: You’ve studied philosophy in Syria and filmmaking in V.G.I.K. Moscow. How did philosophy and Russian schools affect your perception of cinema and the way you make films?

Mohamad: I think the key word in this question is “how”. It made me feel like I am being asked this question for the first time in my life…

If I was affected by my own circumstances, starting the death of my father at a very tender age, working in a poor neighborhood for many years, and the bombing of my hometown, then philosophy has taught me how to think about my experiences and gave me the tools that are necessary to view reality and the world.

In the film institute in Moscow, I learned how to get to know myself visually! And this is all thanks to my five-year mentor. In this period (1969- 1974) and because of the small number of films I had seen, I could not recognize the different film schools. After that, my mentor started liking the ideas I wrote and the pictures I drew. He encouraged me to make films to express myself and my emotional view of what people are enduring in my country. And so I did, in the first three films I made during my studies at the institute. This is what has shaped my style.

I have pursued this style not only in the films I made, but also in the films I most liked, and the filmmakers who have most affected me. Films have affected me more than different film schools.

DFI: As an Arab filmmaker, what were the main challenges you faced in your career?

Mohamad: As a Syrian filmmaker, I have faced nothing but challenges!

I’ve always said that we needed miracles to make films in Syria. The main challenge is the lack of funding. Another challenge is the tight censorship, including our own self-censorship. In addition to all that, we face social and religious censorship… I feel I have never been able to freely make a film. We also face the lack of audience these days!

I have never cared for any technical challenges, although they existed. We were able to solve such issues, as young Syrian filmmakers who started in mid 1970’s, by looking for different expression tools. We didn’t always succeed, but at least we tried… but how can we face the lack of funding? In the beginnings, we had to go through a lot of waiting, patience and work for years on a film project until we were able to make it (maybe once every ten years).

DFI: Your films are critical and socially engaged; do you think films have the means of changing the present?

Mohamad: At first, we were trapped in many illusions. We thought a film could not only change the current situation, but also change the whole political system…. We realized, shortly after, that culture and cinema, if in the right political environment, could affect the people’s awareness and urge them to make changes.

DFI: Between documentaries and fiction. When do you know which format to prefer?

Mohamad: It is true that I studied fiction cinema, but since I came back to my country to make films, I don’t know how this fictional wall separating fiction and documentary collapsed, and cinema was just cinema to me.

This is how I chose to understand cinema!

At first I had to work at a TV station that considered cinema a burden. Only documentaries were allowed, and sometimes short features. Documentaries were not an option at that time. What really defines your choices is the nature of the available opportunities, or what troubles your mind, or the characters you like to present. It is necessary that we know our choices and the reasons behind them at the beginning, but the work style will not differ much, regardless of the choice we make.

When the idea of ‘Al Manam’ (the dream) – which was described by the French magazine ‘Telerama’ as “scarily beautiful”- occurred to me in 1987. In it, Palestinians living in refugee camps in Lebanon tell me the dreams they see in their sleep. I have never imagined that it would be written and acted by the actors.

In my mind, I saw them telling me their dreams. I did not know these were dreams, but I knew the dreams I saw in my sleep. I knew I wanted to make out of their dreams the “nightmare” of my life. I must say that when I finished shooting the film in 1982, and Beirut was invaded, the Sabra & Shatila massacre took the lives of all the characters who told their dreams in front of the camera.

I have mentioned all that in my book ‘Al Manam. A Film Diary’. Because of production issues, the film did not see the light until 1987.

DFI: With the appraisals in the Arab world knowing that the themes of personal freedom and oppression are close to your heart. Do you see hope in the future of Arab cinema?

Mohamad: Deep inside, I believe there is hope. We hope in our ability to change, no matter how long we had to wait for that to happen. That is reason why dictatorships tried to relegate culture and to destroy the real cinema… cinema in Tunisia and Egypt today is different from what is was before the revolutions. I believe that something has changed inside the people living in the Arab world, whether they have succeeded in achieving the change they want yet, or not. People have broken their inner walls.

DFI: What is your message to young filmmakers?

Mohamad: I say please don’t expect and wait for anything to come! Shoot everything you like, express yourselves freely, as you wish and believe and you can. All I ask of you is to give the picture the significance and beauty it deserves, and to realize that the picture has a great and sacred value.

video#1